Factbox

The DST and the South Sulawesi Campaign

- In December 1946 the Dutch military authorities started a twelve week military campaign in the south of Sulawesi (Dutch: Zuid-Celebes). Stakes were high because Sulawesi represented the main interest in the colonial post war era of the Netherlands-Indies.

- The actions were ment to ease violent tensions on Sulawesi and were led by the later iconic Captain Raymond Westerling.

- The Dutch were convinced the isle was on the verge of collapse. Several gangs and disturbers (by the Dutch labelled as 'rampokkers') had disrupted public life in a way that even the Dutch civil and military authorities should fear for their live.

- Westerling, a 27 year old first lieutenant soon to be promoted the youngest captain in the Dutch-Indies army, was allowed to develop his own method, partly derived from Dutch army methods used before 1942.

- In action, Westerling and his 123 men elite unit Depot Speciale Troepen enscenated a local folk tribunal with instant summary right. He believed that executing suspicious people on the spot was the only means to pacifiy the isle. Rule of law, judges, viable proof, a lawyer or rights of appeal were all absent.

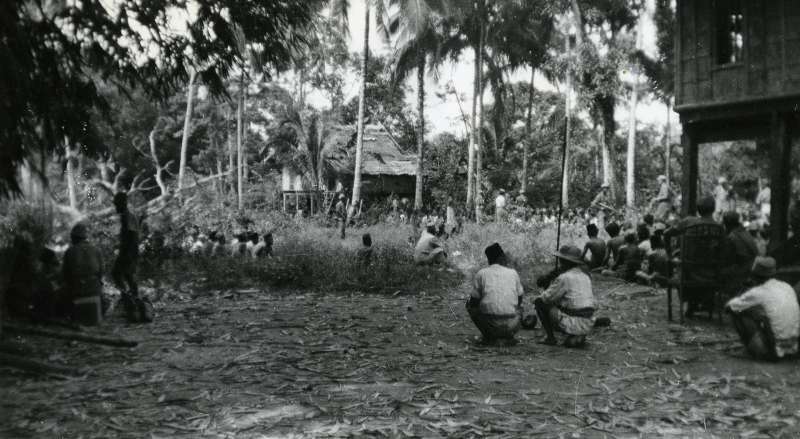

Salomoni, 12 February 1947. Photo by H.C. Kavelaars. Source: Institut Sejarah Militer Belanda.

- From Dutch side, Westerling was praised for his actions. After a few weeks of action several other KNIL commanders insisted on obtaining the right to use summary rights as well.

- Like a virus, violence spread over Sulawesi, first of all at the hands of underlieutenant J.B. Vermeulen, who is mainly associated with actions in Parepare (January 14th, 1947) and Galoeng Lombok (Madjene, February 1st, 1947).

- KNIL Captain Bertold Rijborz and Major Stufkens (both Pinrang and Parepare area) used the summary right as well, as well as some KNIL commanders in the area of Polombangkeng.

- The amount of vicitims will never be clear, but most mentioned numbers are between 563 and 40.000.

- After the special troopers went back to their basis in Jakarta (Polonia) in March 1947, Dutch authorities tried to cover the events and at the same time ordered preliminary judicial investigations by the High Military Court.

- After December 1949, judicial investigations became physically and judicially impossible.

- In 1954 two Dutch lawyers (Van Rij and Stam) finalized a report on behalf of the Dutch Parliament. They concluded that the use of executions was unlawful. The report remained covered until the 90s.

- In 1954 the Dutch Cabinet decided to suspend any court case referring to the Sulawesi military campaign. The arguments were based on three aspects: 1) a formal letter of Recommendation by Westerling’s superior blocked further prosecution of local commanders; 2) political opportunism in the silenced understanding of the colonial past; 3) an alleged agreement between the Netherlands and Indonesia to close colonial court cases forever.